Family Wealth in Three Generations: Fact or Fear Based Marketing?

Marc J. Sharpe & Seth Morton

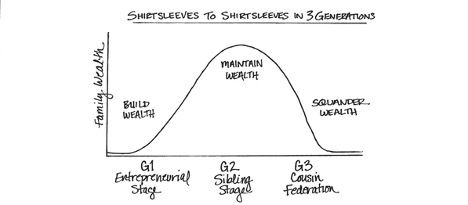

First generation families who are in the process of building a family office often receive the same piece of conventional wisdom: that family wealth passes from “shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in three generations.” A punchier version is also frequently said: “Generation one makes it, Generation two spends it, Generation three blows it.” But where does this ‘universally accepted,’ conventional wisdom come from? And why is it so ubiquitous among family office service providers and wealth advisors in the marketplace?

In 2021, Josh Baron and Rob Lachenauer wrote an article in the family business section of the Harvard Business Review that calls into question the validity of this oft quoted phrase.[1] They go on to question the very foundation upon which so much advice has been rendered to wealthy families looking to build their legacy. For Baron and Lachenauer, the expression traces back to a decades old study of manufacturing companies in Illinois. They also cite other studies regarding the dynamics of multi-generational wealth that suggest wealthy families tend to stay wealthy. Given Baron and Lachenauer’s research, it’s worth reexamining the phrase, both for its value and for the ways it may unfairly or inaccurately portray the dynamics of family wealth. And, of course, we shouldn’t forget how the Estate Planning and Private Wealth ‘industrial complex’ uses this broadly accepted concept to help their clients (and make more money).

While Baron and Lachenauer cite a 1980s study as their starting point for this concept as it relates to family offices, James E. Hughes used this phrase in the beginning of his landmark text Family Wealth, first published in 1997.[2] Hughes used this phrase to not only shape the purpose of his book, but also his entire career. He found both the international character and the utilization of intergenerational dynamics compelling and appropriate for his work. Hughes, and others after him, observed that many cultures have some version of this expression. Indeed, its international ubiquity is quite remarkable. Germanic, Romantic, Slavic, and Asian cultures all seem to possess some version of this expression.

· In China: “From peasant shoes to peasant shoes in three generations.”

· In Mexico: “Father-merchant, son-gentleman, grandson-beggar.

· In Brazil: “Rich father, noble son, poor grandson.”

· In Italy: “From the stables to the stars and back to the stables in three generations.”

For Hughes, this expression speaks to a universal dynamic that informs family wealth. He himself was quite explicit in his writing that the purpose of his life, working with families and family offices, was dedicated to discovering the traits successful families use to break this cycle and to help other families implement best practices so that they might avoid this fate. Anecdotally, he observes a number of families that were unable to overcome this dynamic. Those families splintered and the wealth became fractured and lost. There are innumerable examples of this in the literature. For instance, in 2017 Frances Stroh wrote a heartfelt and personal memoir called Beer Money: A Memoir of Privilege and Loss, which detailed her family’s rise and precipitous fall. Stroh was the heiress to what was at the time the largest private beer company in the United States. Her book details the myriad forces that dismantled her family’s fortune. Some of these were macroeconomic conditions, but many had to do with tensions, disagreements, and losses within the family across multiple generations. Happily, Stroh was able to rebuild a small portion of her family’s wealth and turned it toward reinvestment in Detroit, as well as engagement with non-profits operating in the Detroit area. While Stroh has shared her family story with the public, anyone with experience in the family office world is familiar with stories like hers. Stroh herself said that after publishing the book many people reached out to her to tell their own story of lost family fortunes.[3]

Examples like the Stroh family suggest there is some wisdom within the shirt-sleeves expression. Many of the best practices in family office design are built with an eye toward preparing the next generation of family leadership and helping to enshrine the values of one generation for future generations. This work helps make family offices resilient and dynamic organizations that can evolve and grow over time. However, Baron and Lachenauer are correct to call into question the assumptions that are embedded with this blanket statement. Despite the accepted wisdom the phrase captures, it is often used in a fatalistic fashion, as a scare tactic for any family thinking about creating a family office: “if you don’t listen to our advice, you grandchildren may have nothing”. Sadly, the fatalism of this expression is frequently used as a marketing technique by estate planners and wealth advisors, and as a scare tactic meant to elicit a fear-based response.

The reality is, of course, more complex. According to Gregory Clark, an economist at UC Davis who studies social mobility, when it comes to elite families, the regression to the mean occurs over centuries, not generations. Clark’s study focuses on elite English surnames from the 12th century to the 19th century. He found a remarkably consistent retention of elite status across that 700 year period[4]. Similarly, many of today’s wealthiest families in Italy trace their lineage to the Renaissance[5]. Clearly the picture of dynastic family wealth is more complex than an aphorism about poor tailoring. So, what does this all mean for you and your family office?

First, if someone is using this expression with you, be sure to carefully consider the context and purpose of its use. One should always be wary of those using scare tactics to garner attention and obfuscate rational decision making. Hughes offers the best example of how to use this expression well. For him the expression was just the beginning. The value that he brought to countless families was through the very real and tangible processes and systems he designed to help families govern themselves more effectively. Hughes’ work is not cold and impersonal. As an attorney he understood the formal legal structures that underpin a family office, but he also understood that the legitimacy and efficacy of these structures was more a function of culture and relationships. His work brings to light a humanistic character to family office governance. The ultimate truth that he drew from the “shirtsleeves” expression is that institutional family wealth is made up of individual participants and those individuals have their own ideas, both rational and irrational, that shape how that wealth is managed. Given this understanding, Hughes turned his focus to understanding behavior, looking for models to help each individual achieve their very best.

Second, consider the source. One of the most valuable assets that a new family office can utilize is a trusted peer network of similar families that have managed their generational transition well.[6] In lieu of those networks, finding individuals who have delivered real results in this area is worth much more than an oft cited platitude about multi-generational family wealth transfer.

Finally, while economic data show that family wealth is more resilient than sometimes appears, this doesn’t mean that foundational practices like governance and legacy planning are futile exercises. Devising a plan and creating a culture for rising generations to grow and develop their own form of leadership are essential practices for any family office seeking a multi-generational enterprise. As Hughes’ work shows us, these efforts are more than complex legal structures. They must also put the family and their vison, hopes, and objectives at the center. This shouldn’t be a fear-based process, but rather a deliberate and thoughtful process to enable the very best personal and professional outcomes for your family, business, and family office.

Marc J. Sharpe is the founder and Chairman of TFOA, an organization formed in 2007 to provide a forum for education and networking and to serve as a resource for single family office principals and professionals to share ideas and best practices, pool buying power, leverage talent and conduct due diligence. Mr. Sharpe is active in the community and has served on the Board of the Holocaust Museum Houston, the HBS Houston Angels, and on the Investment Committee for two Texas based foundations.

Seth Morton, Ph.D. has served family offices in areas of investment diligence, execution, and management; governance; research; communications; and multi-generational, sustainable legacy planning. He seeks to improve team performance by cultivating learning-focused and communications- driven processes that deliver exceptional results. He and his family are currently based in Texas.

TFOA is a peer network of Single Family Offices. Our community is intended to provide members with educational information and a forum in which to exchange information of mutual interest. TFOA does not participate in the offer, sale or distribution of any securities nor does it provide investment advice. Further, TFOA does not provide tax, legal or financial advice. Materials distributed by TFOA are provided for informational purposes only and shall not be construed to be a recommendation to buy or sell securities or a recommendation to retain the services of any investment adviser or other professional adviser. The identification or listing of products, services, links, or other information does not constitute or imply any warranty, endorsement, guaranty, sponsorship, affiliation, or recommendation by TFOA. Any investment decisions you may make based on any information provided by TFOA is your sole responsibility. The TFOA logo and all related product and service names, designs, and slogans are the trademarks or service marks of The Family Office Association. All other product and service marks on materials provided by TFOA are the trademarks of their respective owners. All of the intellectual property rights of TFOA or its contributors remain the property of TFOA or such contributor, as the case may be, such rights may be protected by United States and international laws and none of such rights are transferred to you as a result of such material appearing on the TFOA web site. The information presented by TFOA has been obtained by TFOA from sources it believes are reliable. However, TFOA does not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any such information. All such information has been prepared and provided solely for general informational purposes and is not intended as user specific advice.

[1] Josh Baron and Rob Lachenauer, “Do Most Family Businesses Really Fail by the Third Generation?” Harvard Business Review Blog, 19 July 2021. https://hbr.org/2021/07/do-most-family-businesses-really-fail-by-the-third-generation

[2] James E Hughes, Family Wealth: Keeping it in the Family. Bloomberg Press, 1997.

[3] https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/19/your-money/losing-a-fortune-often-comes-down-to-one-thing-family.html

[4] https://www.livescience.com/48951-surnames-social-mobility.html

[5] https://www.vox.com/2016/5/18/11691818/barone-mocetti-florence

[6] In an earlier whitepaper, “Family Office Networks, Clubs, and Associations: What Would Groucho Marx Do?” we provide an analysis of the most common business models for family office networks as well as helpful considerations for each type.