Understanding the Merchant Cash Advance Industry for Single Family Office Investors

By Marc J. Sharpe & ChatGPT

Abstract

This research report analyzes the history, performance, risk, and returns of the merchant cash advance (MCA) industry in the United States. The MCA industry has grown significantly in the past decade, providing small businesses with an alternative to traditional bank loans and family offices with an attractive niche investing strategy. However, the industry has faced some criticism due to its high-interest rates and lack of regulation. Through a review of literature and analysis of industry data, this report presents an overview of the MCA industry, including its history, market size, major stakeholders, risk factors, and financial performance. The report concludes with recommendations for policymakers and family office investors on how to address the risks associated with the MCA industry.

Introduction

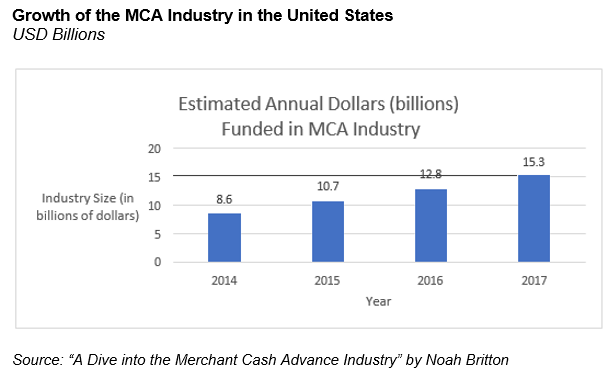

Merchant cash advance (MCA) is a form of alternative financing that provides small businesses with a lump sum payment in exchange for a percentage of future sales. The MCA industry has grown significantly in recent years, with estimates of its market size ranging from $10 billion to $15 billion annually. While MCA has become an attractive financing option for small businesses and family office investors, it has also faced criticism for its high-interest rates and lack of regulation. This research report aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the history, performance, risk, and returns of the MCA industry in the United States.

MCA is a form of financing for small businesses that usually have no other means to borrow money. This is an under-the-radar industry, largely overlooked by academia, media, and government, and as a result has very little regulation. Most lenders in this space are privately-owned (often family offices) and there is little public data on this industry.

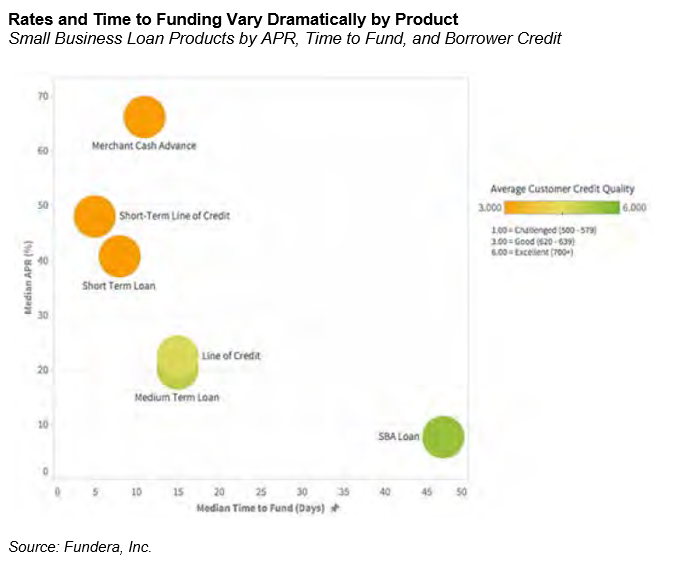

The typical firm taking an MCA is a small-to- medium sized business, often a subprime borrower, often paying a much higher interest rate than a typical business loan. It is estimated that in 2016 MCA borrowing summed to around $10 billion, with a default rate up to 600% higher than loans from the U.S. Small Business Administration. Many borrowers find MCA to be a last resort option, if they are unable to get a loan from a bank and because “cheaper loans backed by the Small Business Administration are tough to get and can take months to close.”

History of the MCA Industry

The MCA industry emerged in the early 2000s as a response to the difficulties small businesses faced in obtaining traditional bank loans. The MCA industry began by offering cash advances to small businesses in exchange for a fixed percentage of future credit and debit card sales. This model proved successful and expanded to include other forms of payment, such as ACH transfers. The MCA industry has continued to grow as a result of the continued difficulties small businesses face in obtaining traditional bank loans, particularly in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis.

The merchant cash advance industry is relatively new. MCAs are only possible with the advent of digital payments. In some ways they can be thought of as the technological successor to factoring. Credit cards became widespread in the 1990s, and the MCA industry closely followed. It is believed that AdvanceMe in Georgia became the first MCA provider in 1998. Originally, AdvanceMe had a patent on MCA technology, which meant it was the only provider at that time. In 2007, a Texas judge invalidated AdvanceMe’s patent on cash advances against future credit card transactions, allowing new MCA firms to compete.

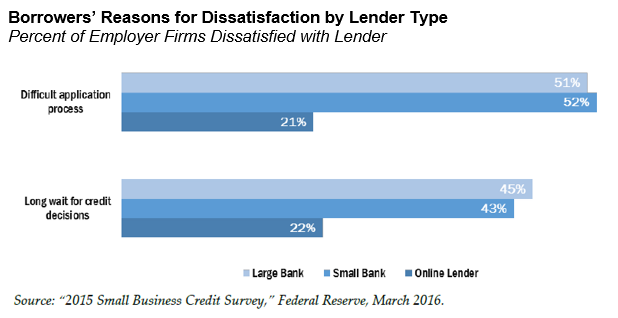

Within the next year, the 2008 crisis and following recession greatly changed the financial system. Firstly, banks as a whole became more reluctant to underwrite loans. Loans were risky, and after the housing and financial system collapse, banks were risk averse. Secondly, the banking system saw consolidation. Large banks absorbed many smaller regional ones. Between 1998 and 2015, the number of small banks decreased by 38%. Small regional banks have traditionally been, and still are, more willing to lend to small and medium sized businesses, as compared to large, multinational banks. Historically, big banks approve roughly 22% of small business loans, compared to small banks approving 49%. The effect of the financial crisis was therefore twofold: banks reduced lending to small businesses overall due to uncertainty in the economy, and small banks which are more likely to lend to small businesses were replaced with large banks.

In addition, regulation and compliance costs disincentivize big banks from lending to small businesses because the regulatory costs are not worth these small dollar loans. For a small bank, the dollar amount of a small business loan is more meaningful to the bottom line of the firm. The aftermath of the financial crisis led to more regulations, exacerbating this issue. Legislation like Basel III and Dodd-Frank made the financial industry more cumbersome, which to some extent reduced small business lending.

Overall, small business lending has declined throughout the United States over the past decade. As a result of these changes, many small businesses are unable to obtain a traditional loan from a bank. Their need for financing still exists, however, so small businesses are forced to look for alternative ways to borrow money. This has led to the merchant cash advance industry becoming increasingly popular.

Market Size and Major Stakeholders

The MCA industry has grown significantly in the past decade, with estimates of its market size ranging from $10 billion to $15 billion annually. Private companies dominate the industry, with the largest players including CAN Capital, OnDeck, and RapidAdvance. However, the MCA industry has also attracted the attention of ‘disruptive technology’ public companies, such as Square and PayPal, who have begun to offer their own MCA products. In addition to private and public companies, the major stakeholders in the MCA industry include small businesses, funders, and brokers.

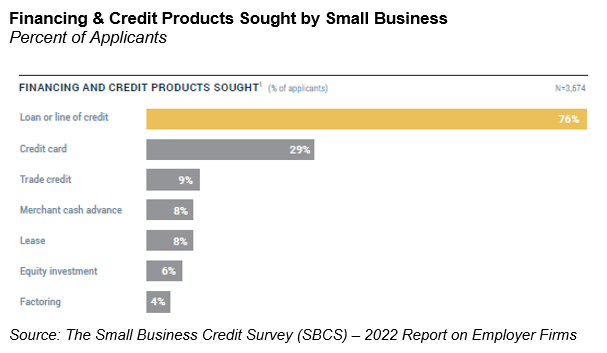

The Small Business Credit Survey (SBCS) is a collaboration of all 12 Federal Reserve Banks and provides timely information about small business conditions to policymakers and lenders, including an annual survey of firms with fewer than 500 employees. These types of firms represent 99.7% of all employer establishments in the United States.

In 2021, the survey found that application rates for traditional financing were lower in 2021 than in recent years, and those that did apply were less likely to receive the financing they sought. The share of firms seeking traditional financing fell from 43% in 2019 to 34% in 2021. One beneficiary of this reduced demand for traditional credit is the MCA industry which, according to the SBCS survey, now comprises 8% of financing sought by small businesses.

While the MCA industry is still a small percentage of the overall lending in the United States, at an estimated $15.3 billion in 2017 it is clearly emerging as an important growth segment for small and medium sized businesses.

Origination

Merchant cash advance providers source their clients in one of two ways, each making up around half of the advances in the industry. The first is directly, meaning their internal marketing team will find merchants in need of an advance. The second is through an Independent Sales Organization (ISO). Both methods involve cold calling and paid outreach to small businesses. The ISOs will charge the MCA provider a one-time commission, usually around 5-10% of the advance amount.

As part of the underwriting process, MCA providers conduct a due diligence. This may involve analyzing bank statements, monthly credit card sales volume, the age of the company, and the rent-to-sales ratio, among other things. With an MCA ‘advance’ a business will receive a lump sum of capital and will pay back a multiple of that amount with automatic daily deductions until it is paid off. These ‘advances’ are typically short-term, with little paperwork involved, and the money is received in as fast as 24 hours.

By way of example, in a typical MCA the borrower will receive a lump sum, say $100,000. The borrower will owe an amount larger than the amount received. This figure will be equal to the advance amount times the buy rate, also known as the factor rate. In this example, the borrower will repay $135,000. because the buy rate is 1.35x on $100,000. The terms of the MCA specify how the advance will be repaid. Unlike a traditional loan, the borrower does not pay the lender in fixed amounts. Instead, the borrower repays the MCA with automatic electronic payments. More specifically, a designated percentage of daily, weekly, or monthly credit card sales will be directly sent to the MCA provider until the borrower pays the entire payback amount.

Notice how words like “interest rate,” “debt,” or “loan” are not used to describe an MCA. This is because an MCA is classified as an “advance” rather than a “loan.” Even though a loan and an MCA both involve receiving a sum of money that must be paid off, regulators do not consider an MCA a loan. In effect, MCA’s “aren’t actually charging interest—they’re buying the money businesses will make in the future, at a discount.”

Although it seems like a pedantic distinction, by not being classified as a loan MCAs avoid the laws and regulations associated with lending. For example, banks that lend are subject to Dodd-Frank and Basel III, which include capital and disclosure requirements, whereas MCAs are not. In addition, MCA providers are not subject to usury laws, which limit the maximum percentage of interest that can legally be charged. Therefore, MCA providers can charge whatever APR equivalent they desire without disclosing it to the borrower. This has been proven in court as recently as 2018. Champion Auto Sales, LLC et al. v Pearl Beta Funding, LLC in the state of New York found (in a unanimous decision) that MCA lending above the usurious limit is permitted.

Risk Factors

MCA firms are buying the rights to the future receivables of their customers. As a result, if the customer finds that it cannot pay back the loan or that the repayment on each transaction becomes too high, it may cease operations so that there are no more future receivables. And since it is not debt, the “lender” has no claims to the assets during bankruptcy or liquidation. Therefore, MCAs are riskier than debt, which means lenders need to be compensated accordingly.

Some commentators have criticized the MCA industry due to its high-interest rates and lack of regulation. The effective interest rates on MCA loans, given their short duration, can be very high, which has led to concerns about predatory lending practices. In addition, the lack of regulation in the MCA industry means that borrowers may not have the same protections as those who obtain traditional bank loans. The lack of transparency in MCA loan agreements has also led to concerns about hidden fees and charges.

By the same token, concerns are also raised about the high cost of short-term lending products now being offered by online lending platforms. Providers of these loans explain that the APR is an annual cost and overstates the actual expense, or dollar cost, of a loan that is only in place for typically less than twelve months. Some industry observers have raised concerns that costs at this level are very hard for a small business to manage in a profitable way. They argue that a small business needs to generate a very high return in a very short period, or they risk the consequence of being unable to repay. On the other hand, these loans or advances are valuable for a small business that, for example, needs to buy inventory for the holiday season or bridge a seasonal cash shortage.

In all cases, to minimize defaults it is clearly important that small businesses understand in a clear fashion the product obligations they are committing to take on, including exactly how much they are paying.

Financial Performance

Despite the risks associated with the MCA industry, it has demonstrated strong financial performance in recent years. The average annual return on MCA investments is estimated to be between 15% and 40%. This high return has attracted a range of investors, including private equity firms and hedge funds. However, the high returns come with significant risks, and investors should be aware of the potential for losses due to default or fraud.

MCAs serve a purpose. If a business needs quick capital to cover liquidity needs and no bank approves their application, it often has no other option than an MCA. The industry exists because small businesses that cannot borrow through traditional finance need to borrow money.

Conclusion

The MCA industry has provided small businesses with an alternative to traditional bank loans but has also faced criticism for its high-interest rates and lack of regulation. This research report has presented a comprehensive analysis of the history, performance, risk, and returns of the MCA industry in the United States. Policymakers should consider regulating the industry to ensure that borrowers are protected from predatory lending practices and have the same rights as those who obtain traditional bank loans. Investors should be aware of the risks.

Arguably, MCAs have a niche in the economy because of government regulation. Usury laws prevent banks from charging their risk-adjusted required rate of return from small business loans, so they opt to not lend to these businesses. Banking regulations have made it difficult for small banks to compete with big banks, while simultaneously disincentivizing small business lending with onerous requirements. The Small Business Administration is unable to provide adequate loans to all the small businesses in need. If banks can charge higher interest rates or are otherwise incentivized to lend to small businesses, this might reduce the market for MCAs. Additionally, new disruptive technology like peer-to-peer and decentralized blockchain lending pose a potential alternative.

Banning the MCA industry outright would mean that many small businesses would lose their only source of financing. Regulators must legislate on the fine line between protecting borrowers, while at the same time ensuring that these borrowers do not lose their existing lenders of last resort.

Bibliography

· “It’s Settled, Merchant Cash Advance Not Usurious | DeBanked.” Accessed May 5, 2021. https://debanked.com/2018/03/its-settled-merchant-cash-advance-not-usurious/.

· Stevens, Jordan. “The Merchant Cash Advance Industry May Have a Few Bad Apples, but That Does Not Mean It’s Time to Empty the Barrel Comments.” Texas Tech Law Review 49, no. 2 (2017 2016): 501–46.

· “What Is MCA ‘Stacking’ and Why We Discourage It?” Accessed May 5, 2021. https://www.elevatefunding.com/post/what-is-mca-stacking-and-why-we-discourage-it.

· “A Dive into the Merchant Cash Advance Industry” by Noah Britton (Leonard N. Stern School of Business)

· “BPC-MCA-SMB-Financing-Industry-Report.Pdf.” Accessed May 5, 2021. https://bryantparkcapital.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/BPC-MCA-SMB-Financing- Industry-Report.pdf.

· Dabertin 1, Troutman Pepper-Mark T., and Gregory J. Nowak. “Merchant Cash Advance Participations and the Federal Securities Laws | Lexology.” Accessed May 5, 2021.

· “FTC Alleges Merchant Cash Advance Provider Overcharged Small Businesses Millions | Federal Trade Commission.” Accessed May 5, 2021.

· The State of Small Business Lending: Innovation and Technology and the Implications for Regulation by Karen Gordon Mills & Brayden McCarthy (Harvard Business School)

· Small Business Credit Survey – 2022 Report on Employer Firms (Federal Reserve Banks)

Marc J. Sharpe is the founder and Chairman of The Family Office Association (“TFOA”), an organization formed in 2007 to provide a forum for education and networking and to serve as a resource for single family office principals and professionals to share ideas and best practices, pool buying power, leverage talent and conduct due diligence. Mr. Sharpe is active in the community and has served on the Board of the Holocaust Museum Houston, the HBS Houston Angels, and on the Investment Committee for two Texas based foundations. Contact: marc@tfoatx.com

The Family Office Association ("TFOA") is a peer network of Single Family Offices. Our community is intended to provide members with educational information and a forum in which to exchange information of mutual interest. TFOA does not participate in the offer, sale or distribution of any securities nor does it provide investment advice. Further, TFOA does not provide tax, legal or financial advice. Materials distributed by TFOA are provided for informational purposes only and shall not be construed to be a recommendation to buy or sell securities or a recommendation to retain the services of any investment adviser or other professional adviser. The identification or listing of products, services, links, or other information does not constitute or imply any warranty, endorsement, guaranty, sponsorship, affiliation, or recommendation by TFOA. Any investment decisions you may make based on any information provided by TFOA is your sole responsibility. The TFOA logo and all related product and service names, designs, and slogans are the trademarks or service marks of TFOA. All other product and service marks on materials provided by TFOA are the trademarks of their respective owners. All of the intellectual property rights of TFOA or its contributors remain the property of TFOA or such contributor, as the case may be, such rights may be protected by United States and international laws and none of such rights are transferred to you as a result of such material appearing on the TFOA web site. The information presented by TFOA has been obtained by TFOA from sources it believes are reliable. However, TFOA does not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any such information. All such information has been prepared and provided solely for general informational purposes and is not intended as user specific advice.